Difference between revisions of "Readings/Godard Since 1968 and Claire Denis"

(added History of Cameroon) |

(added May 1968 Events in France) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

]] | ]] | ||

[[Image:Bundesarchiv Bild 163-051, Kamerun, Weihnachten am Mungo.jpg|thumb|German Settlers celebrating [[Christmas]] in Kamerun]] | [[Image:Bundesarchiv Bild 163-051, Kamerun, Weihnachten am Mungo.jpg|thumb|German Settlers celebrating [[Christmas]] in Kamerun]] | ||

| − | |||

Beginning on July 5, 1884, all of present-day Cameroon and parts of several of its neighbours became [[German colonial empire|a German colony]], [[Kamerun]], with a capital first at [[Buea]] and later at [[Yaoundé]]. | Beginning on July 5, 1884, all of present-day Cameroon and parts of several of its neighbours became [[German colonial empire|a German colony]], [[Kamerun]], with a capital first at [[Buea]] and later at [[Yaoundé]]. | ||

| Line 57: | Line 56: | ||

In early 2006 a final resolution to the dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria over the oil-rich [[Bakassi peninsula]] was expected. In October 2002, the International Court of Justice had ruled in favour of Cameroon. Nonetheless, a lasting solution would require agreement by both countries’ presidents, parliaments, and by the [[United Nations]]. The peninsula was the site of fighting between the two countries in 1994 and again in June 2005, which led to the death of a Cameroonian soldier. In 2006, Nigerian troops left the peninsula. | In early 2006 a final resolution to the dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria over the oil-rich [[Bakassi peninsula]] was expected. In October 2002, the International Court of Justice had ruled in favour of Cameroon. Nonetheless, a lasting solution would require agreement by both countries’ presidents, parliaments, and by the [[United Nations]]. The peninsula was the site of fighting between the two countries in 1994 and again in June 2005, which led to the death of a Cameroonian soldier. In 2006, Nigerian troops left the peninsula. | ||

| + | |||

| + | =May 1968 Events in France= | ||

| + | {{Infobox civil conflict | ||

| + | | title = May 1968 events in France | ||

| + | | partof = [[Protests of 1968]] | ||

| + | | image = 1968-05 Évènements de mai à Bordeaux - Rue Paul-Bert 1.jpg | ||

| + | | caption = [[Barricades]] in [[Bordeaux]] in May 1968. | ||

| + | | date = 2 May – 23 June 1968<br/>({{Age in years, months, weeks and days|year1=1968|month1=05|day1=02|year2=1968|month2=6|day2=23}}) | ||

| + | | place = France | ||

| + | | coordinates = | ||

| + | | causes = | ||

| + | | goals = | ||

| + | | methods = [[Occupation (protest)|Occupation]]s, [[Wildcat strike action|wildcat strike]]s, [[general strike]]s | ||

| + | | status = | ||

| + | | result = [[French legislative election, 1968|Snap legislative election]] | ||

| + | | side1 = Students | ||

| + | *[[Union Nationale des Étudiants de France]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Unions | ||

| + | *[[Confédération générale du travail|CGT]] | ||

| + | *[[Workers' Force|FO]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Anarchists]]<br />[[French Communist Party]]<br />[[Situationist International]]<br/> [[Federation of the Democratic and Socialist Left]] | ||

| + | | side2 = {{flagicon|France|size=16px}} '''[[Cabinet of France|Government of France]]''' | ||

| + | *[[Minister of the Interior (France)|Ministry of the Interior]] | ||

| + | **{{flagicon image|Badge - Police Nationale.jpg}} [[National Police (France)|Police nationale]] | ||

| + | **{{flagicon image|Ecussoncrs.jpg}} [[Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité]] | ||

| + | *[[French Armed Forces]] | ||

| + | *[[Union of Democrats for the Republic|Gaullist Party]] | ||

| + | | side3 = | ||

| + | | leadfigures1 = '''Non-centralized leadership'''<br />[[François Mitterrand]]<br />[[Pierre Mendès France]] | ||

| + | | leadfigures2 = '''[[Charles de Gaulle]]'''<br /><small>([[President of France]])</small><br />[[Georges Pompidou]]<br /><small>([[Prime Minister of France]])</small> | ||

| + | | leadfigures3 = | ||

| + | | howmany1 = | ||

| + | | howmany2 = | ||

| + | | howmany3 = | ||

| + | | casualties1 = | ||

| + | | casualties2 = | ||

| + | | casualties3 = | ||

| + | | fatalities = | ||

| + | | injuries = | ||

| + | | arrests = | ||

| + | | detentions = | ||

| + | | casualties_label = | ||

| + | | notes = | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | {{Students rights sidebar}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | The volatile period of [[civil unrest]] in [[France]] during May 1968 was punctuated by demonstrations and massive [[general strike]]s as well as the [[Occupation (protest)|occupation]] of universities and [[Occupation of factories|factories]] across France. At the height of its fervor, it brought the entire [[economy of France]] to a virtual halt.<ref name="SitInt12"/> The protests reached such a point that political leaders feared [[civil war]] or [[French Revolution (disambiguation)|revolution]]; the national government itself momentarily ceased to function after President [[Charles de Gaulle]] secretly fled France for a few hours. The protests spurred an artistic movement, with songs, imaginative graffiti, posters, and slogans.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.deljehier.levillage.org/mai_68.htm |title=Mai 68 - 40 ans déjà |publisher=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://www.cambridge.org/us/academic/subjects/arts-theatre-culture/western-art/museum-establishment-and-contemporary-art-politics-artistic-display-france-after-1968?format=PB|title=The Museum Establishment and Contemporary Art: The Politics of Artistic Display in France after 1968|last=DeRoo|first=Rebecca J.|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2014|isbn=9781107656918|location=|pages=}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | "May 68" affected French society for decades afterward. It is considered to this day as a cultural, social and moral turning point in the history of the country. As Alain Geismar—one of the leaders of the time—later pointed out, the movement succeeded "as a social revolution, not as a political one".<ref name="Erlanger 2008"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The unrest began with a series of [[Student protest|student occupation protests]] against [[anticapitalism|capitalism]], [[consumerism]], [[American imperialism]] and traditional institutions, values and order. It then spread to factories with [[Strike action|strikes]] involving 11 million workers, more than 22% of the total [[Demographics of France|population of France]] at the time, for two continuous weeks.<ref name="SitInt12">{{cite web |url=http://www.cddc.vt.edu/sionline/si/beginning.html |title=Situationist International Online |publisher=}}</ref> The movement was characterized by its spontaneous and [[Decentralization#Government decentralization|de-centralized]] [[wildcat strike action|wildcat]] disposition; this created contrast and sometimes even conflict between itself and the establishment, [[trade union]]s and workers' parties.<ref name="SitInt12"/> It was the largest general strike ever attempted in France, and the first nationwide wildcat general strike.<ref name="SitInt12"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The student occupations and wildcat general strikes initiated across France were met with forceful confrontation by university administrators and police. The de Gaulle administration's attempts to quell those strikes by [[Riot control|police action]] only inflamed the situation further, leading to street battles with the police in Paris's [[Latin Quarter]], followed by the spread of general strikes and occupations throughout France. De Gaulle fled to a French military base in Germany, and after returning dissolved the [[French National Assembly|National Assembly]], and called for [[French legislative election, 1968|new parliamentary elections]] for 23 June 1968. Violence evaporated almost as quickly as it arose. Workers went back to their jobs, and when the elections were finally held in June, the Gaullist party emerged even stronger than before. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Events before May== | ||

| + | In February 1968, the [[French Communist Party|French Communists]] and [[French Socialist Party|French Socialists]] formed an electoral alliance. Communists had long supported Socialist candidates in elections, but in the "February Declaration" the two parties agreed to attempt to form a joint government to replace [[President of France|President]] Charles de Gaulle and his [[Gaullist Party]].{{r|mendel196901}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | On 22 March far-left groups, a small number of prominent poets and musicians, and 150 students occupied an administration building at [[Paris X University Nanterre|Paris University at Nanterre]] and held a meeting in the university council room dealing with class discrimination in French society and the political bureaucracy that controlled the university's funding. The university's administration called the police, who surrounded the university. After the publication of their wishes, the students left the building without any trouble. After this first record some leaders of what was named the "[[Movement of 22 March]]" were called together by the disciplinary committee of the university. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Events of May== | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Student strikes=== | ||

| + | [[File:SorbonneParis041130.JPG|thumb|Public square of [[Sorbonne (building)|the Sorbonne]], in the Latin Quarter of Paris]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following months of conflicts between students and authorities at the Nanterre campus of the [[University of Paris]] (now [[Paris Nanterre University]]), the administration shut down the university on 2 May 1968.<ref>Rotman, pp. 10–11; Damamme, Gobille, Matonti & Pudal, ed., p. 190.</ref> Students at the Sorbonne campus of the University of Paris (today [[Sorbonne University]]) in Paris met on 3 May to protest against the closure and the threatened expulsion of several students at Nanterre.<ref>Damamme, Gobille, Matonti & Pudal, ed., p. 190.</ref> On Monday, 6 May, the national student union, the [[Union Nationale des Étudiants de France]] (UNEF)—still the largest student union in France today—and the union of university teachers called a march to protest against the police invasion of Sorbonne. More than 20,000 students, teachers and supporters marched towards the Sorbonne, still sealed off by the police, who charged, wielding their batons, as soon as the marchers approached. While the crowd dispersed, some began to create barricades out of whatever was at hand, while others threw paving stones, forcing the police to retreat for a time. The police then responded with tear gas and charged the crowd again. Hundreds more students were arrested. | ||

| + | |||

| + | {{multiple image | ||

| + | | direction = vertical | ||

| + | | width = 180 | ||

| + | | footer = [[University of Lyon]] during student occupation, May–June 1968 | ||

| + | | image1 = Graffito_in_University_of_Lyon_classroom_during_student_revolt_of_1968.jpg | ||

| + | | alt1 = | ||

| + | | caption1 = [[Graffiti|Wall slogan]] in a classroom | ||

| + | | image2 = University_of_Lyon_Law_School_with_graffiti_June_1968.jpg | ||

| + | | alt2 = | ||

| + | | caption2 = "Vive De Gaulle" is one of the graffiti on this Law School building. | ||

| + | | image3 = | ||

| + | | alt3 = | ||

| + | | caption3 = | ||

| + | }} | ||

| + | |||

| + | High school student unions spoke in support of the riots on 6 May. The next day, they joined the students, teachers and increasing numbers of young workers who gathered at the [[Arc de Triomphe]] to demand that: | ||

| + | # All criminal charges against arrested students be dropped, | ||

| + | # the police leave the university, and | ||

| + | # the authorities reopen Nanterre and Sorbonne. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Negotiations broke down, and students returned to their campuses after a false report that the government had agreed to reopen them, only to discover the police still occupying the schools. This led to a near revolutionary fervor among the students. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On Friday, 10 May, another huge crowd congregated on the [[Rive Gauche]]. When the [[Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité]] again blocked them from crossing the river, the crowd again threw up barricades, which the police then attacked at 2:15 in the morning after negotiations once again floundered. The confrontation, which produced hundreds of arrests and injuries, lasted until dawn of the following day. The events were broadcast on radio as they occurred and the aftermath was shown on television the following day. Allegations were made that the police had participated in the riots, through ''[[agents provocateurs]]'', by burning cars and throwing [[Molotov cocktail]]s.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.lemonde.fr/web/article/0,1-0@2-3476,36-885493,0.html |title=Michel Rocard : |work=Le Monde.fr}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The government's heavy-handed reaction brought on a wave of sympathy for the strikers. Many of the nation's more mainstream singers and poets joined after the police brutality came to light. American artists also began voicing support of the strikers. The major left union federations, the [[Confédération Générale du Travail]] (CGT) and the [[Force Ouvrière]] (CGT-FO), called a one-day general strike and demonstration for Monday, 13 May. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Well over a million people marched through Paris on that day; the police stayed largely out of sight. Prime Minister [[Georges Pompidou]] personally announced the release of the prisoners and the reopening of the Sorbonne. However, the surge of strikes did not recede. Instead, the protesters became even more active. | ||

| + | |||

| + | When the Sorbonne reopened, students occupied it and declared it an autonomous "people's university". Public opinion at first supported the students, but quickly turned against them after their leaders, invited to appear on national television, "behaved like irresponsible utopianists who wanted to destroy the 'consumer society.'"{{r|dogan1984}} Nonetheless, in the weeks that followed, approximately 401 popular action committees were set up in Paris and elsewhere to take up grievances against the government and French society, including the [[Occupation Committee of the Sorbonne|Sorbonne Occupation Committee]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Workers join the students=== | ||

| + | {{refimprove section|date=May 2017}} | ||

| + | In the following days, workers began occupying factories, starting with a sit-down strike at the [[Sud Aviation]] plant near the city of [[Nantes]] on 14 May, then another strike at a [[Renault]] parts plant near [[Rouen]], which spread to the Renault manufacturing complexes at Flins in the Seine Valley and the Paris suburb of [[Boulogne-Billancourt]]. Workers had occupied roughly fifty factories by 16 May, and 200,000 were on strike by 17 May. That figure snowballed to two million workers on strike the following day and then ten million, or roughly two-thirds of the French workforce, on strike the following week. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:French workers with placard during occupation of their factory 1968.jpg|thumb|left|Strikers in [[Southern France]] with a sign reading "Factory Occupied by the Workers." Behind them is a list of demands, June 1968.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | These strikes were not led by the union movement; on the contrary, the CGT tried to contain this spontaneous outbreak of militancy by channeling it into a struggle for higher wages and other economic demands. Workers put forward a broader, more political and more radical agenda, demanding the ousting of the government and President de Gaulle and attempting, in some cases, to run their factories. When the trade union leadership negotiated a 35% increase in the minimum wage, a 7% wage increase for other workers, and half normal pay for the time on strike with the major employers' associations, the workers occupying their factories refused to return to work and jeered their union leaders.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/27424054|title=Enragés and situationists in the occupation movement, France, May '1968|last=1944-|first=Viénet, René,|date=1992|publisher=Autonomedia|year=|isbn=0936756799|location=New York|pages=91|oclc=27424054}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.de/books?id=6IjRojUCS8gC&pg=PA195|title=Prelude to Revolution: France in May 1968|last=Singer|first=Daniel|date=2002|publisher=South End Press|year=|isbn=9780896086821|location=|pages=184–185|language=en}}</ref> In fact, in the May '68 movement there was a lot of "anti-unionist euphoria,"<ref name="Derrida91MagLitEwald">[[Derrida|Derrida, Jacques]] (1991) ''"A 'Madness' Must Watch Over Thinking"'', interview with [[Francois Ewald]] for ''Le Magazine Litteraire'', March 1991, republished in ''[[Points...: Interviews, 1974-1994]]'' (1995).pp.347-9</ref> against the mainstream unions, the CGT, FO and CFDT, that were more willing to compromise with the powers that be than enact the will of the base.<ref name="SitInt12"/> | ||

| + | |||

| + | On 24 May two people died at the hands of the out of control rioters, in Lyon Police Inspector Rene Lacroix died when he crushed by a driverless truck sent careering into police lines by rioters and in Paris Phillipe Metherion, 26, was stabbed to death during an argument among demonstrators.<ref>https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=3rNVAAAAIBAJ&sjid=GOEDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6508%2C6329247</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | On 25 May and 26 May, the [[Grenelle agreements]] were conducted at the [[Minister of Social Affairs (France)|Ministry of Social Affairs]]. They provided for an increase of the minimum wage by 25% and of average salaries by 10%. These offers were rejected, and the strike went on. The working class and top intellectuals were joining in solidarity for a major change in workers' rights. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On 27 May, the meeting of the UNEF, the most outstanding of the events of May 1968, proceeded and gathered 30,000 to 50,000 people in the [[Stade Sebastien Charlety]]. The meeting was extremely militant with speakers demanding the government be overthrown and elections held. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Socialists saw an opportunity to act as a compromise between de Gaulle and the Communists. On 28 May, [[François Mitterrand]] of the [[Federation of the Democratic and Socialist Left]] declared that "there is no more state" and stated that he was ready to form a new government. He had received a surprisingly high 45% of the vote in the [[French presidential election, 1965|1965 presidential election]]. On 29 May, [[Pierre Mendès France]] also stated that he was ready to form a new government; unlike Mitterrand he was willing to include the Communists. Although the Socialists did not have the Communists' ability to form large street demonstrations, they had more than 20% of the country's support.{{r|dogan1984}}{{r|mendel196901}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===De Gaulle flees=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | On the morning of 29 May, de Gaulle postponed the meeting of the [[Council of Ministers of France|Council of Ministers]] scheduled for that day and secretly removed his personal papers from [[Élysée Palace]]. He told his son-in-law [[Alain de Boissieu]], "I do not want to give them a chance to attack the Élysée. It would be regrettable if blood were shed in my personal defense. I have decided to leave: nobody attacks an empty palace." De Gaulle refused Pompidou's request that he dissolve the [[National Assembly of France|National Assembly]] as he believed that their party, the Gaullists, would lose the resulting election. At 11:00 a.m., he told Pompidou, "I am the past; you are the future; I embrace you."<ref name="dogan1984">{{Cite journal |last=Dogan |first=Mattei |title=How Civil War Was Avoided in France |journal=International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique |year=1984 |volume=5 |issue=3 |pages=245–277 |jstor=1600894|doi=10.1177/019251218400500304}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The government announced that de Gaulle was going to his country home in [[Colombey-les-Deux-Églises]] before returning the next day, and rumors spread that he would prepare his resignation speech there. The presidential helicopter did not arrive in Colombey, however, and de Gaulle had told no one in the government where he was going. For more than six hours the world did not know where the French president was.<ref name="singer2002">{{cite book |title=Prelude to Revolution: France in May 1968 |publisher=South End Press |last=Singer |first=Daniel |year=2002 |url=https://books.google.com/?id=6IjRojUCS8gC&pg=PA195 |isbn=978-0-89608-682-1 |pages=195, 198–201}}</ref> The canceling of the ministerial meeting, and the president's mysterious disappearance, stunned the French,{{r|dogan1984}} including Pompidou, who shouted, "He has fled the country!"<ref name="dogan2005">{{cite book |title=Political Mistrust and the Discrediting of Politicians |publisher=Brill |author=Dogan, Mattéi |year=2005 |pages=218 |isbn=9004145303}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The national government had effectively ceased to function. [[Édouard Balladur]] later wrote that as prime minister, Pompidou "by himself was the whole government" as most officials were "an incoherent group of confabulators" who believed that revolution would soon occur. A friend of the prime minister offered him a weapon, saying, "You will need it"; Pompidou advised him to go home. One official reportedly began burning documents, while another asked an aide how far they could flee by automobile should revolutionaries seize fuel supplies. Withdrawing money from banks became difficult, gasoline for private automobiles was unavailable, and some people tried to obtain private planes or fake [[National identity card (France)|national identity card]]s.{{r|dogan1984}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | Pompidou unsuccessfully requested that military radar be used to follow de Gaulle's two helicopters, but soon learned that he had gone to the headquarters of the French military in Germany, in [[Baden-Baden]], to meet General [[Jacques Massu]]. Massu persuaded the discouraged de Gaulle to return to France; now knowing that he had the military's support, de Gaulle rescheduled the meeting of the Council of Ministers for the next day, 30 May,{{r|dogan1984}} and returned to Colombey by 6:00 p.m.{{r|singer2002}} [[Yvonne de Gaulle|His wife Yvonne]] gave the family jewels to [[Philippe de Gaulle|their son and daughter-in-law]]—who stayed in Baden for a few more days—for safekeeping, however, indicating that the de Gaulles still considered Germany a possible refuge. Massu kept as a [[Classified information|state secret]] de Gaulle's loss of confidence until others disclosed it in 1982; until then most observers believed that his disappearance was intended to remind the French people of what they might lose. Although the disappearance was real and not intended as motivation, it indeed had such an effect on France.{{r|dogan1984}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:Pierre Messmer01.JPG|thumb|upright|[[Pierre Messmer]]]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | On 30 May, 400,000 to 500,000 protesters (many more than the 50,000 the police were expecting) led by the CGT marched through Paris, chanting: "''Adieu, de Gaulle!''" ("Farewell, de Gaulle!"). [[Maurice Grimaud]], head of the [[Prefecture of Police|Paris police]], played a key role in avoiding revolution by both speaking to and spying on the revolutionaries, and by carefully avoiding the use of force. While Communist leaders later denied that they had planned an armed uprising, and extreme militants only comprised 2% of the populace, they had overestimated de Gaulle's strength as shown by his escape to Germany.{{r|dogan1984}} (One scholar, otherwise skeptical of the French Communists' willingness to maintain democracy after forming a government, has claimed that the "moderate, nonviolent and essentially antirevolutionary" Communists opposed revolution because they sincerely believed that the party must come to power through legal elections, not armed conflict that might provoke harsh repression from political opponents.)<ref name="mendel196901">{{cite journal |jstor=1406452 |title=Why the French Communists Stopped the Revolution |last=Mendel |first=Arthur P. |journal=The Review of Politics |date=January 1969 |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=3–27 |doi=10.1017/s0034670500008913}}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The movement was largely centered around the [[Paris metropolitan area]], and not elsewhere. Had the rebellion occupied key public buildings in Paris, the government would have had to use force to retake them. The resulting casualties could have incited a revolution, with the military moving from the provinces to retake Paris [[Paris Commune|as in 1871]]. [[Minister of Defence (France)|Minister of Defence]] Pierre Messmer and [[Chief of the Defence Staff (France)|Chief of the Defence Staff]] Michel Fourquet prepared for such an action, and Pompidou had ordered tanks to [[Issy-les-Moulineaux]].{{r|dogan1984}} While the military was free of revolutionary sentiment, using an army mostly of conscripts the same age as the revolutionaries would have been very dangerous for the government.{{r|mendel196901}}{{r|singer2002}} A survey taken immediately after the crisis found that 20% of Frenchmen would have supported a revolution, 23% would have opposed it, and 57% would have avoided physical participation in the conflict. 33% would have fought a military intervention, while only 5% would have supported it and a majority of the country would have avoided any action.{{r|dogan1984}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | At 2:30 p.m. on 30 May, Pompidou persuaded de Gaulle to dissolve the National Assembly and call a new election by threatening to resign. At 4:30 p.m., de Gaulle broadcast his own refusal to resign. He announced an election, scheduled for 23 June, and ordered workers to return to work, threatening to institute a [[state of emergency]] if they did not. The government had leaked to the media that the army was outside Paris. Immediately after the speech, about 800,000 supporters marched through the Champs-Élysées waving the [[Flag of France|national flag]]; the Gaullists had planned the rally for several days, which attracted a crowd of diverse ages, occupations, and politics. The Communists agreed to the election, and the threat of revolution was over.{{r|dogan1984}}{{r|singer2002}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://membres.lycos.fr/mai68/degaulle/degaulle30mai1968.htm |title=Lycos |publisher= |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090422060607/http://membres.lycos.fr/mai68/degaulle/degaulle30mai1968.htm |archivedate=22 April 2009 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Events of June and July== | ||

| + | |||

| + | From that point, the revolutionary feeling of the students and workers faded away. Workers gradually returned to work or were ousted from their plants by the police. The national student union called off street demonstrations. The government banned a number of leftist organizations. The police retook the Sorbonne on 16 June. Contrary to de Gaulle's fears, his party won the greatest victory in French parliamentary history in the [[French legislative election, 1968|legislative election held in June]], taking 353 of 486 seats versus the Communists' 34 and the Socialists' 57.{{r|dogan1984}} The February Declaration and its promise to include Communists in government likely hurt the Socialists in the election. Their opponents cited the example of the [[National Front (Czechoslovakia)|Czechoslovak National Front]] government of 1945, which led to a [[Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948|Communist takeover of the country]] in 1948. Socialist voters were divided; in a February 1968 survey a majority had favored allying with the Communists, but 44% believed that Communists would attempt to seize power once in government. (30% of Communist voters agreed.){{r|mendel196901}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | On [[Bastille Day]], there were resurgent street demonstrations in the Latin Quarter, led by socialist students, leftists and communists wearing red arm-bands and anarchists wearing black arm-bands. The Paris police and the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité harshly responded starting around 10 pm and continuing through the night, on the streets, in police vans, at police stations, and in hospitals where many wounded were taken. There was, as a result, much bloodshed among students and tourists there for the evening's festivities. No charges were filed against police or demonstrators, but the governments of Britain and [[West Germany]] filed formal protests, including for the indecent assault of two English schoolgirls by police in a police station. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Despite the size of de Gaulle's triumph, it was not a personal one. The post-crisis survey showed that a majority of the country saw de Gaulle as too old, too self-centered, too authoritarian, too conservative, and too [[anti-Americanism|anti-American]]. As the [[French constitutional referendum, 1969|April 1969 referendum]] would show, the country was ready for "Gaullism without de Gaulle".{{r|dogan1984}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Slogans and graffiti== | ||

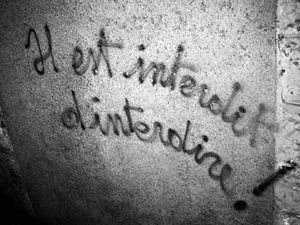

| + | [[File:Situationist.jpg|thumb|May 1968 slogan. Paris. "It is forbidden to forbid."]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | A few examples:<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.bopsecrets.org/French/graffiti.htm |title=Graffiti de Mai 1968 |publisher=}}</ref> | ||

| + | *''Il est interdit d'interdire'' ("It is forbidden to forbid").<ref name="larousse.fr">{{cite web|url=http://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/divers/%C3%A9v%C3%A9nements_de_mai_1968/131140|title=Encyclopédie Larousse en ligne - événements de mai 1968|author=Éditions Larousse|publisher=|accessdate=29 September 2015}}</ref> | ||

| + | *''Jouissez sans entraves'' ("Enjoy without hindrance").<ref name="larousse.fr"/> | ||

| + | *''Élections, piège à con'' ("Elections, a trap for idiots").<ref>{{cite web|url=http://tempsreel.nouvelobs.com/l-observateur-de-la-gauche-radicale/20120228.OBS2484/pour-la-gauche-radicale-elections-piege-a-cons.html|title=Pour la gauche radicale, "élections, piège à cons" ?|author=Par Sylvain BoulouqueVoir tous ses articles|date=28 February 2012|work=L'Obs|accessdate=29 September 2015}}</ref> | ||

| + | * ''[[Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité|CRS]] = [[Waffen-SS|SS]]''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lexpress.fr/informations/crs-ss_628697.html|title=CRS = SS|publisher=|accessdate=29 September 2015}}</ref> | ||

| + | * ''Je suis Marxiste—tendance Groucho''. ("I'm a [[Marxism|Marxist]]—of the [[Groucho Marx|Groucho]] tendency.")<ref>{{cite book |title=The Concise Dictionary of Foreign Quotations |last=Lejeune |first=Anthony |year=2001 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=0953330001 |page=74 |url=https://books.google.com/?id=3KLz2QEdQaoC&pg=PA74 |accessdate=1 December 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | *''Marx, Mao, [[Herbert Marcuse|Marcuse]]!''<ref>{{cite book |title=Dialectical Imagination |url=https://books.google.com/?id=tTyHOxeCiG4C&pg=PR12&dq=%22Marx/Mao/Marcuse%22 |page=xii |year=1996 |author=Martin Jay}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=How Language, Ritual and Sacraments Work: According to John Austin, Jürgen Habermas and Louis-Marie Chauvet |url=https://books.google.com/?id=AJWTVXRnn00C&pg=PA80&dq=%22Marx,+Mao,+Marcuse%22 |page=80 |author=Mervyn Duffy |access-date=9 March 2015 |isbn=9788878390386 |year=2005 |publisher=Gregorian Biblical BookShop}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Contemporary Social Theory: An Introduction |url=https://books.google.com/?id=ETnIAgAAQBAJ&pg=66&dq=%22Marx,+Mao+and+Marcuse%22 |page=66 |author=Anthony Elliott |access-date=9 March 2015 |year=2014}}</ref> Also known as "3M".<ref>{{cite journal |title=''Power and Protest: Global Revolution and the Rise of Détente'' by Jeremi Suri |first=Roberto |last=Franzosi |journal=American Journal of Sociology |volume=111 |number=5 |page=1589 |date=March 2006 |jstor=10.1086/504653 |publisher=The University of Chicago Press |doi=10.1086/504653}}</ref> | ||

| + | * ''Cela nous concerne tous.'' ("This concerns all of us.") | ||

| + | * ''Soyez réalistes, demandez l'impossible''. ("Be realistic, ask the impossible.")<ref>{{cite book |title=The Language of Change: Elements of Therapeutic Communication |last=Watzlawick |first=Paul |year=1993 |publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |isbn=9780393310207 |page=83 |url=https://books.google.com/?id=4U2ItyNGvecC&pg=PA83 |accessdate=1 December 2010}}</ref> | ||

| + | * "When the National Assembly becomes a bourgeois theater, all the bourgeois theaters should be turned into national assemblies." (Written above the entrance of the occupied [[Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe|Odéon]] Theater)<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/154668230|title=Revolutionary rehearsals|last=|first=|date=2002|publisher=Haymarket Books|others=Barker, Colin, 1939-|year=|isbn=9781931859028|location=Chicago, Il.|page=|pages=23|oclc=154668230}}</ref> | ||

| + | * ''Sous les pavés, la plage!'' ("Under the paving stones, the beach.") | ||

| + | * "I love you!!! Oh, say it with paving stones!!!"<ref name="Knabb">{{cite book |title=Situationist International Anthology |editor=Ken Knabb |year=2006 |publisher=Bureau Of Public Secrets |isbn=9780939682041}}</ref> | ||

| + | * "Read [[Wilhelm Reich|Reich]] and act accordingly!" (University of Frankfurt; similar Reichian slogans were scrawled on the walls of the Sorbonne, and in Berlin students threw copies of Reich's ''[[The Mass Psychology of Fascism]]'' (1933) at the police).<ref>Turner, Christopher (2011). ''Adventures in the Orgasmatron''. HarperCollins, pp. 13–14.</ref> | ||

| + | * ''Travailleurs la lutte continue[;] constituez-vous en comité de base.'' ("Workers the fight continues; form a basic committee.")<ref>https://www.google.com/search?biw=1440&bih=738&ei=omA8W5HsGsaKjwT405foDg&q=travailleurs+la+lutte+continue&oq=travailleurs+la+lutte+continue&gs_l=psy-ab.3..33i160k1.429.7026.0.7316.34.33.1.0.0.0.146.3024.22j9.31.0..2..0...1.1.64.psy-ab..2.28.2649...0j0i131k1j0i131i67k1j0i10k1j0i19k1j0i22i30i19k1j0i22i30k1j33i22i29i30k1j33i21k1.0.f8JFzpzyQQI</ref><ref>https://www.gerrishfineart.com/mai-68,-%27travailleurs-la-lutte-continue%27,-screenprint,-1968~1795</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Legacy== | ||

| + | {{Libertarian socialism|Events}} | ||

| + | May 1968 is an important reference point in French politics, representing for some the possibility of liberation and for others the dangers of anarchy.<ref name="Erlanger 2008">{{cite news |last=Erlanger |first=Steven |title=May 1968 - a watershed in French life |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/29/world/europe/29iht-france.4.12440504.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all |accessdate=31 August 2012 |newspaper=New York Times |date=29 April 2008}}</ref> For some, May 1968 meant the end of traditional collective action and the beginning of a new era to be dominated mainly by the so-called [[new social movements]].<ref>Staricco, Juan Ignacio (2012) https://www.scribd.com/doc/112409042/The-French-May-and-the-Roots-of-Postmodern-Politics</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Someone who took part in or supported this period of unrest is referred to as [[Wiktionary:soixante-huitard|soixante-huitard]] - a term, derived from the French for "68", which has also entered the English language. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == In popular culture == | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Cinema=== | ||

| + | * The [[François Truffaut]] film ''[[Baisers volés]]'' (1968) (in English: "Stolen Kisses"), takes place in Paris during the time of the riots and while not an overtly political film, there are passing references to and images of the demonstrations. The film captures the revolutionary feel of the time and makes perfectly understandable why Truffaut and [[Jean-Luc Godard]] would call for the cancellation of the Cannes Film Festival of 1968. Nothing could go on as it had in the past after May '68, and "Stolen Kisses" itself was a statement of that refusal.{{Citation needed|date=October 2018}} | ||

| + | * The [[André Cayatte]] film ''[[:fr:Mourir d'aimer (film, 1971)|Mourir d'aimer]]'' (1971) (in English: "To die of love") is strongly based on the true story of [[:fr:Gabrielle Russier|Gabrielle Russier]] (1937-1969), a classics teacher (played by [[Annie Girardot]]) who committed suicide after being sentenced for having had an affair with one of her students during the events of May 68. | ||

| + | * The [[Jean-Luc Godard]] film ''[[Tout Va Bien]]'' (1972) examines the continuing [[class struggle]] within French society in the aftermath of May '68. | ||

| + | * [[Jean Eustache]]'s 1973 film ''[[The Mother and the Whore]]'', winner of the [[Grand Prix (Cannes Film Festival)|Cannes Grand Prix]], references the events of May 1968 and explores the aftermath of the social movement.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://sensesofcinema.com/2014/2014-melbourne-international-film-festival-dossier/the-mother-and-the-whore/ |title=The Mother and the Whore |last=Pierquin |first=Martine |date=July 2014 |accessdate=1 June 2017 |work=[[Senses of Cinema]]}}</ref> | ||

| + | * The [[Claude Chabrol]] film ''[[Nada (1974 film)|Nada]]'' 1974 is based symbolically on the events of May 1968. | ||

| + | * The [[Diane Kurys]] film ''Cocktail Molotov'' (1980) tells the story of a group of French friends heading towards Israel when they hear of the May events and decide to return to Paris. | ||

| + | * The [[Louis Malle]] film ''[[May Fools]]'' (1990) is a satiric depiction of the effect of French revolutionary fervor of May 1968 on small-town bourgeoisie. | ||

| + | * The [[Bernardo Bertolucci]] film ''[[The Dreamers (film)|The Dreamers]]'' (2003), based on the novel ''[[The Holy Innocents (Adair novel)|The Holy Innocents]]'' by [[Gilbert Adair]], tells the story of an American university student in Paris during the protests. | ||

| + | * The [[Philippe Garrel]] film ''[[Regular Lovers]]'' (2005) is about a group of young people participating in the Latin Quarter of Paris barricades and how they continue their life one year after. | ||

| + | * In the spy-spoof, ''[[OSS 117: Lost in Rio]]'', the lead character Hubert ironically chides the hippie students, saying, 'It's 1968. There will be no revolution. Get a haircut.' | ||

| + | * The [[Olivier Assayas|Oliver Assayas]] film ''[[Something in the Air (2012 film)|Something in the Air]]'' (2012) tells the story of a young painter and his friends who bring the revolution to their local school and have to deal with the legal and existential consequences. | ||

| + | * ''[[Redoubtable (film)|Le Redoutable]]'', 2017 - bio-pic of Jean-Luc Godard, covering the 1968 riots/Cannes festival etc. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Music=== | ||

| + | * Many writings of French [[anarchist]] [[singer-songwriter]] [[Léo Ferré]] were inspired by those events. Songs directly related to May 1968 are: "L'Été 68", "Comme une fille" (1969), "[[Amour Anarchie|Paris je ne t'aime plus]]" (1970), "[[La Violence et l'Ennui]]" (1971), "[[Il n'y a plus rien]]" (1973), "La Nostalgie" (1979). Many others Ferré's songs share the libertarian feel of that time. | ||

| + | * [[Claude Nougaro]]'s song "Paris Mai" (1969).<ref>{{Cite news|issn=0362-4331|last=Riding|first=Alan|title=Claude Nougaro, French Singer, Is Dead at 74|work=The New York Times|accessdate=2015-11-23|date=2004-03-22|url= https://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/22/arts/claude-nougaro-french-singer-is-dead-at-74.html}}</ref> | ||

| + | * The imaginary Italian clerk described by [[Fabrizio de André]] in his album ''Storia di un impiegato'', is inspired to build a bomb set to explode in front of the Italian parliament by listening to reports of the May events in France, drawn by the perceived dullness and repetitivity of his life compared to the revolutionary developments unfolding in France.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Giannini|first1=Stefano|title=Storia di un impiegato di Fabrizio De André|work=La Riflessione|date=2005|pages=11–16}}</ref> | ||

| + | * The [[Refused]] song entitled "Protest Song '68" is about the May 1968 protests.<ref>{{Cite book|publisher=Lexington Books|isbn=978-0-7391-4276-9|last1=Kristiansen|first1=Lars J.|last2=Blaney|first2=Joseph R.|last3= Chidester|first3=Philip J.|last4=Simonds|first4=Brent K.|title=Screaming for Change: Articulating a Unifying Philosophy of Punk Rock| date = 2012-07-10}}</ref> | ||

| + | * [[The Stone Roses]]'s song "Bye Bye Badman", from their [[The Stone Roses (album)|eponymous album]], is about the riots. The album's cover has the ''tricolore'' and lemons on the front (which were used to nullify the effects of tear gas).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.john-squire.com/art/gallery_byebyebadman.html |title=Bye Bye Badman |publisher=John Squire |author=John Squire |accessdate=3 November 2009}}</ref> | ||

| + | * The music video for the [[David Holmes (musician)|David Holmes]] song "I Heard Wonders" is based entirely on the May 1968 protests and alludes to the influence of the [[Situationist International]] on the movement.<ref>{{Cite web| last = Cole| first = Brendan|title=David Holmes Interview|work=RTE.ie|format=Articles|accessdate=2015-11-23|date=2008-08-25|url=http://www.rte.ie/ten/features/2008/0825/414398-davidholmes/}}</ref> | ||

| + | *[[The Rolling Stones]] wrote the lyrics to the song "[[Street Fighting Man]]" (set to music of an unreleased song they had already written which had different lyrics) in reference to the May 1968 protests from their perspective, living in a "sleepy London town". The melody of the song was inspired by French police car sirens.<ref>"I wanted the [sings] to sound like a French police siren. That was the year that all that stuff was going on in Paris and in London. There were all these riots that the generation that I belonged to, for better or worse, was starting to get antsy. You could count on somebody in America to find something offensive about something — you still can. Bless their hearts. I love America for that very reason." {{Cite web|last=N.P.R.Staff|title=Keith Richards: 'These Riffs Were Built To Last A Lifetime'|work=NPR.org|accessdate=2015-11-23|url= https://www.npr.org/2012/11/13/165033885/keith-richards-these-riffs-were-built-to-last-a-lifetime}}</ref> | ||

| + | *[[Vangelis]] released an album in France and Greece entitled ''[[Fais que ton rêve soit plus long que la nuit]]'' ("May you make your dreams longer than the night"), which was about the Paris student riots in 1968. The album contains sounds from the demonstrations, songs, and a news report. Vangelis would later become famous for film scores for such films as Chariots of Fire and Bladerunner.<ref>{{Cite book|publisher=Lulu Press, Inc|isbn=978-1-4476-2728-9|last=Griffin|first=Mark J. T.|title=Vangelis: The Unknown Man|date=2013-03-13}}</ref> | ||

| + | *[[Ismael Serrano]]'s song "Papá cuéntame otra vez" ("Papa, tell me again") references the May 1968 events: "Papa, tell me once again that beautiful story, of gendarmes and fascists and long-haired students; and sweet urban war in flared trousers, and songs of the Rolling stones, and girls in miniskirts."<ref>{{Cite web|last=Mucientes|first=Esther|title=MAYO DEL 68: La música de la revolución|work=elmundo.es|accessdate=2015-11-23|url= http://www.elmundo.es/especiales/2008/04/internacional/mayo_68/canciones/cancion02.html}}</ref> | ||

| + | *[[Caetano Veloso]]'s song "É Proibido Proibir" takes its title from the May 1968 graffiti of the same name and was a protest song against the [[Brazilian military government|military regime]] that assumed power in Brazil in April 1964.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Brutality Garden: Tropicalia and the Emergence of a Brazilian Counterculture|last=Christopher|first=Dunn|publisher=University of North Carolina Press|year=2001|isbn=|location=|pages=135|quote=|via=}}</ref> | ||

| + | *Many of the slogans from the May 1968 riots were included in [[Luciano Berio]]'s seminal work ''[[Sinfonia (Berio)|Sinfonia]]''. | ||

| + | *The band [[Orchid (hardcore punk band)|Orchid]] references the events of May 68 as well as [[Guy Debord|Debord]] in their song "Victory Is Ours". | ||

| + | *[[The 1975]]'s song "[[Love It If We Made It]]" makes reference to the Atelier Populaire's book made to support the events, '[[Beauty Is in the Street|Beauty Is In The Street]]'. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Literature=== | ||

| + | * The 1971 novel ''[[The Merry Month of May (novel)|The Merry Month of May]]'' by [[James Jones (author)|James Jones]] tells a story of (fictional) American expatriates caught up in Paris during the events. | ||

| + | * ''[[The Holy Innocents (Adair novel)|The Holy Innocents]]'' is a 1988 novel by [[Gilbert Adair]] with a climactic finale on the streets of 1968 Paris. The novel was adapted for the screen as ''[[The Dreamers (film)|The Dreamers]]'' (2003). | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Art=== | ||

| + | *The painting [[May 1968 (Miró)|''May 1968'']], by Spanish painter [[Joan Miró]], was inspired by the events in May 1968 in France. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Video games=== | ||

| + | *The 2010 game ''Metal Gear Solid: Peace Walker'' had a briefing file that described the May 1968 protests and their influence on the character Cécile Cosima Caminades, a Frenchwoman. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Sources== | ||

| + | {{Refbegin}} | ||

| + | *{{cite book |title=Mai-juin 68 |year=2008 |publisher=Éditions de l'Atelier |isbn=978-2708239760 |editor1=Damamme, Dominique |editor2=Gobille, Boris |editor3=Matonti, Frédérique |editor4=Pudal, Bernard |language=French}} | ||

| + | *{{cite book |last=Rotman |first=Patrick |title=Mai 68 raconté à ceux qui ne l'ont pas vécu |year=2008 |publisher=Seuil |isbn=978-2021127089 |language=French}} | ||

| + | {{Refend|colwidth=30em}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Further reading== | ||

| + | *Abidor, Mitchell. ''May Made Me. An Oral History of the 1968 Uprising in France'' (interviews). | ||

| + | *Adair, Gilbert. ''The Holy Innocents'' (novel). | ||

| + | *[[Julian Bourg|Bourg, Julian]]. ''From Revolution to Ethics: May 1968 and Contemporary French Thought''. | ||

| + | *Casevecchie, Janine. ''MAI 68 en photos:'',Collection Roger-Viollet, Editions du Chene - Hachette Livre, 2008. | ||

| + | *[[Cornelius Castoriadis|Castoriadis, Cornelius]] with [[Claude Lefort]] and [[Edgar Morin]]. ''Mai 1968: la brèche''. | ||

| + | *[[Tony Cliff|Cliff, Tony]] and [[Ian Birchall]]. ''France – the struggle goes on''. [http://www.marx.org/archive/cliff/works/1968/france/index.htm Full text at marx.org] | ||

| + | *[[Daniel Cohn-Bendit|Cohn-Bendit, Daniel]]. ''Obsolete Communism: The Left-Wing Alternative''. | ||

| + | *Dark Star Collective. ''Beneath the Paving Stones: Situationists and the Beach, May 68''. | ||

| + | *DeRoo, Rebecca J. ''The Museum Establishment and Contemporary Art: The Politics of Artistic Display in France after 1968''. | ||

| + | *Feenberg, Andrew and Jim Freedman. ''When Poetry Ruled the Streets''. | ||

| + | *[[Lawrence Ferlinghetti|Ferlinghetti, Lawrence]]. ''Love in the Days of Rage'' (novel). | ||

| + | *Gregoire, Roger and [[Fredy Perlman|Perlman, Fredy]]. ''Worker-Student Action Committees: France May '68''. [https://libcom.org/files/Worker-student%20action%20committees,%20France%20May%20%2768%20-%20Roger%20Gregoire%20and%20Fredy%20Perlman.pdf PDF of the text] | ||

| + | *[[Chris Harman|Harman, Chris]]. ''The Fire Last Time: 1968 and After''. London: Bookmarks, 1988. | ||

| + | *Jones, James. ''The Merry Month of May'' (novel). | ||

| + | *[[Ken Knabb|Knabb, Ken]]. ''[[Situationist International Anthology]]''. | ||

| + | *[[Mark Kurlansky|Kurlansky, Mark]]. ''1968: The Year That Rocked The World''. | ||

| + | *[[Greil Marcus|Marcus, Greil]]. ''[[Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the 20th Century]]''. | ||

| + | * Emile Perreau-Saussine, "Liquider mai 68?", in Les droites en France (1789–2008), CNRS Editions, 2008, p. 61-68, [https://web.archive.org/web/20110719141447/http://www.polis.cam.ac.uk/contacts/staff/eperreausaussine/liquider_mai_68.pdf PDF] | ||

| + | *[[Sadie Plant|Plant, Sadie]]. ''[[The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist International in a Postmodern Age]]''. | ||

| + | *{{cite book |last1=Quattrochi |first1=Angelo |last2=Nairn |first2=Tom |title=The Beginning of the End |publisher=[[Verso Books]] |year=1998 |isbn=978-1859842904 }} | ||

| + | *[[Kristin Ross|Ross, Kristin]]. ''May '68 and its Afterlives''. | ||

| + | *Schwarz, Peter. [http://www.wsws.org/articles/2008/may2008/may1-m28.shtml '1968: The general strike and the student revolt in France']. 28 May 2008. Retrieved 12 June 1010. [[World Socialist Web Site]]. | ||

| + | *[[Patrick Seale|Seale, Patrick]] and Maureen McConville. ''Red Flag/Black Flag: French Revolution 1968''. | ||

| + | *Seidman, Michael. ''The Imaginary Revolution: Parisian Students and Workers in 1968'' (Berghahn, 2004). | ||

| + | *[[Daniel Singer (journalist)|Singer, Daniel]]. ''Prelude To Revolution: France In May 1968''. | ||

| + | *Staricco, Juan Ignacio. ''[https://www.scribd.com/doc/94247008/The-French-May-and-the-Shift-of-Paradigm-of-Collective-Action The French May and the Shift of Paradigm of Collective Action]''. | ||

| + | *[[Alain Touraine|Touraine, Alain]]. ''The May Movement: Revolt and Reform''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | {{Commons category|May 1968 protests in France}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Archival collections=== | ||

| + | *[http://www.oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt196nc927/ Guide to the Paris Student Revolt Collection.] Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California. | ||

| + | *[http://digitalcollections.vicu.utoronto.ca/RS/pages/search.php?search=special:paris%20posters Paris 1968 Posters] Digital Collections | Victoria University Library in the University of Toronto | ||

| + | *[http://library.vicu.utoronto.ca/collections/special_collections/paris_posters/ Paris, Posters of a Revolution Collection] Special Collections | Victoria University Library in the University of Toronto | ||

| + | *[http://edocs.lib.sfu.ca/projects/mai68/ May Events Archive of Documents] | ||

| + | *[https://www.marxists.org/history/france/may-1968/index.htm Paris May-June 1968 Archive] at [[marxists.org]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Others=== | ||

| + | *[http://city-journal.org/2008/18_2_spring_1968.html May 1968: 40 Years Later, ''City Journal,'' Spring 2008] | ||

| + | *[http://libcom.org/library/May-68-Solidarity Maurice Brinton, Paris May 1968] | ||

| + | *[http://www.sens-public.org/spip.php?article472 Chris Reynolds, ''May 68: A Contested History'', ''Sens Public''] | ||

| + | *[https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=90330162 Marking the French Social Revolution of 1968], an NPR audio report | ||

| + | *[https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/30/world/europe/30france.html?_r=1&oref=slogin Barricades of May ’68 Still Divide the French] New York Times | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | {{reflist|colwidth=30em}} | ||

Revision as of 16:48, 28 November 2018

History of Cameroon

Colonization

Beginning on July 5, 1884, all of present-day Cameroon and parts of several of its neighbours became a German colony, Kamerun, with a capital first at Buea and later at Yaoundé.

The imperial German government made substantial investments in the infrastructure of Cameroon, including the extensive railways, such as the 160-metre single-span railway bridge on the South Sanaga River branch. Hospitals were opened all over the colony, including two major hospitals at Douala, one of which specialised in tropical diseases. However, the indigenous peoples proved reluctant to work on these projects, so the Germans instigated a harsh and unpopular system of forced labour.[1] In fact, Jesko von Puttkamer was relieved of duty as governor of the colony due to his untoward actions toward the native Cameroonians.[2] In 1911 at the Treaty of Fez after the Agadir Crisis, France ceded a nearly 300,000 km² portion of the territory of French Equatorial Africa to Kamerun which became Neukamerun, while Germany ceded a smaller area in the north in present-day Chad to France.

In World War I, the British invaded Cameroon from Nigeria in 1914 in the Kamerun campaign, with the last German fort in the country surrendering in February 1916. After the war, this colony was partitioned between the United Kingdom and France under June 28, 1919 League of Nations mandates (Class B). France gained the larger geographical share, transferred Neukamerun back to neighboring French colonies, and ruled the rest from Yaoundé as Cameroun (French Cameroons). Britain's territory, a strip bordering Nigeria from the sea to Lake Chad, with an equal population was ruled from Lagos as Cameroons (British Cameroons). German administrators were allowed to once again run the plantations of the southwestern coastal area. A British parliamentary publication, Report on the British Sphere of the Cameroons (May 1922, p. 62-8), reports that the German plantations there were "as a whole . . . wonderful examples of industry, based on solid scientific knowledge. The natives have been taught discipline and have come to realize what can be achieved by industry. Large numbers who return to their villages take up cocoa or other cultivation on their own account, thus increasing the general prosperity of the country."

Towards Independence (1955-1960)

On 18 December 1956, the outlawed Union of the Peoples of Cameroon (UPC), based largely among the Bamileke and Bassa ethnic groups, began an armed struggle for independence in French Cameroon. This rebellion continued, with diminishing intensity, even after independence until 1961.[3] Some tens of thousands died during this conflict.[4][5]

Legislative elections were held on 23 December 1956 and the resulting Assembly passed a decree on 16 April 1957 which made French Cameroon a State. It took back its former status of associated territory as a member of the French Union. Its inhabitants became Cameroonian citizens, Cameroonian institutions were created under the sign of parliamentary democracy. On 12 June 1958 the Legislative Assembly of French Cameroon asked the French government to: 'Accord independence to the State of Cameroon at the ends of their trusteeship. Transfer every competence related to the running of internal affairs of Cameroon to Cameroonians`. On 19 October 1958 France recognized the right of her United Nations trust territory of the Cameroons to choose independence.[6] On 24 October 1958 the Legislative Assembly of French Cameroon solemnly proclaimed the desire of Cameroonians to see their country accede full independence on 1 January 1960. It enjoined the government of French Cameroon to ask France to inform the General Assembly of the United Nations, to abrogate the trusteeship accord concomitant with the independence of French Cameroon. On 12 November 1958 having accorded French Cameroon total internal autonomy and thinking that this transfer no longer permitted it to assume its responsibilities over the trust territory for an unspecified period, the government of France asked the United Nations to grant the wish of French Cameroonians. On 5 December 1958 the United Nations’ General Assembly took note of the French government’s declaration according to which French Cameroon, which was under French administration, would gain independence on 1 January 1960, thus marking an end to the trusteeship period.[7][8] On 13 March 1959 the United Nations’ General Assembly resolved that the UN Trusteeship Agreement with France for French Cameroon would end when French Cameroon became independent on 1 January 1961.[9]

Cameroon after independence

French Cameroon achieved independence on January 1, 1960 as La Republique du Cameroun. After Guinea, it was the second of France's colonies in Sub-Saharan Africa to become independent. On 21 February 1960, the new nation held a constitutional referendum. On 5 May 1960, Ahmadou Ahidjo became president. On 11 February 1961, a plebiscite organised by the United Nations was held in the British controlled part of Cameroon (British Northern and British Southern Cameroons). The pleibiscite was to choose between free association with an independent Nigerian state or re-unification with the independent Republic of Cameroun. On 12 February 1961,the results of the plebiscite were released and British Northern Cameroons attached itself to Nigeria, while the southern part voted for reunification with the Republic Of Cameroon. To negotiate the terms of this union, the Foumban Conference was held on 16–21 July 1961. John Ngu Foncha, the leader of the Kamerun National Democratic Party . The British Southern Cameroons was to be referred to as West Cameroon and the French part as East Cameroon. Buea became the capital of the now West Cameroon while Yaounde doubled as the federal capital and East Cameroon. Ahidjo accepted the federation, thinking it was a step towards a unitary state. On 14 August 1961, the federal constitution was adopted, with Ahidjo as president. Foncha became the prime minister of west Cameroon and vice president of the Federal Republic of Cameroon. On 1 September 1966 the Cameroon National Union (CNU) was created by the union of political parties of East and West Cameroon. Most decisions about West Cameroon were taken without consultation, which led to widespread feelings amongst the West Cameroonian public that although they voted for reunification, what they were getting is absorption or domination".[10]

On October 1, 1961, the largely Muslim northern two-thirds of British Cameroons voted to join Nigeria; the largely Christian southern third, Southern Cameroons, voted, in a referendum, to join with the Republic of Cameroon to form the Federal Republic of Cameroon. The formerly French and British regions each maintained substantial autonomy. Ahidjo was chosen president of the federation in 1961. In 1962, the Francs CFA became the official currency in Cameroon.

Ahidjo, relying on a pervasive internal security apparatus, outlawed all political parties but his own in 1966. He successfully suppressed the continuing UPC rebellion, capturing the last important rebel leader in 1970. On 28 March 1970 Ahidjo renewed his mandate as the supreme magistracy; Solomon Tandeng Muna became Vice President. In 1972, a new constitution replaced the federation with a unitary state called the United Republic of Cameroon. Although Ahidjo's rule was characterised as authoritarian, he was seen as noticeably lacking in charisma in comparison to many post-colonial African leaders. He didn't follow the anti-western policies pursued by many of these leaders, which helped Cameroon achieve a degree of comparative political stability and economic growth.

On 30 June 1975 Paul Biya was appointed vice president. Ahidjo resigned as president in 1982 and was constitutionally succeeded by his Prime Minister, Paul Biya, a career official. Ahidjo later regretted his choice of successors, but his supporters failed to overthrow Biya in a 1984 coup. Biya won single-candidate elections in 1983 and 1984 when the country was again named the Republic of Cameroon. Biya has remained in power, winning flawed multiparty elections in 1992, 1997, 2004 and 2011. His Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM) party holds a sizeable majority in the legislature.

By April 6, 1984, the country witnessed its first coup d'état headed by col. Issa Adoum. At about 3 am rebel forces mostly of the Republican guard under the orders of colonel Ibrahim Saleh, attempted to unseat Biya's government. The rebels took charge of the Yaounde airport, national radio station and announced the takeover of government. They attacked the presidency. The civilian northerner who was manager of FONADER Issa Adoum was expected to become the new interim president. Unfortunately, many reasons led to its failure. The principal coup plotters had been arrested by April 10, 1984 and President Biya addressed the nation that calm had been restored.

On August 15, 1984, Lake Monoun exploded in a limnic eruption that released carbon dioxide, suffocating 37 people to death. On August 21, 1986, another limnic eruption at Lake Nyos killed as many as 1,800 people and 3,500 livestock. The two disasters are the only recorded instances of limnic eruptions.

In May 2014, in the wake of the Chibok schoolgirl kidnapping, Presidents Paul Biya of Cameroon and Idriss Déby of Chad announced they were waging war on Boko Haram, and deployed troops to the Nigerian border.[11][12]

In early 2006 a final resolution to the dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria over the oil-rich Bakassi peninsula was expected. In October 2002, the International Court of Justice had ruled in favour of Cameroon. Nonetheless, a lasting solution would require agreement by both countries’ presidents, parliaments, and by the United Nations. The peninsula was the site of fighting between the two countries in 1994 and again in June 2005, which led to the death of a Cameroonian soldier. In 2006, Nigerian troops left the peninsula.

May 1968 Events in France

Template:Infobox civil conflict Template:Students rights sidebar

The volatile period of civil unrest in France during May 1968 was punctuated by demonstrations and massive general strikes as well as the occupation of universities and factories across France. At the height of its fervor, it brought the entire economy of France to a virtual halt.[13] The protests reached such a point that political leaders feared civil war or revolution; the national government itself momentarily ceased to function after President Charles de Gaulle secretly fled France for a few hours. The protests spurred an artistic movement, with songs, imaginative graffiti, posters, and slogans.[14][15]

"May 68" affected French society for decades afterward. It is considered to this day as a cultural, social and moral turning point in the history of the country. As Alain Geismar—one of the leaders of the time—later pointed out, the movement succeeded "as a social revolution, not as a political one".[16]

The unrest began with a series of student occupation protests against capitalism, consumerism, American imperialism and traditional institutions, values and order. It then spread to factories with strikes involving 11 million workers, more than 22% of the total population of France at the time, for two continuous weeks.[13] The movement was characterized by its spontaneous and de-centralized wildcat disposition; this created contrast and sometimes even conflict between itself and the establishment, trade unions and workers' parties.[13] It was the largest general strike ever attempted in France, and the first nationwide wildcat general strike.[13]

The student occupations and wildcat general strikes initiated across France were met with forceful confrontation by university administrators and police. The de Gaulle administration's attempts to quell those strikes by police action only inflamed the situation further, leading to street battles with the police in Paris's Latin Quarter, followed by the spread of general strikes and occupations throughout France. De Gaulle fled to a French military base in Germany, and after returning dissolved the National Assembly, and called for new parliamentary elections for 23 June 1968. Violence evaporated almost as quickly as it arose. Workers went back to their jobs, and when the elections were finally held in June, the Gaullist party emerged even stronger than before.

Events before May

In February 1968, the French Communists and French Socialists formed an electoral alliance. Communists had long supported Socialist candidates in elections, but in the "February Declaration" the two parties agreed to attempt to form a joint government to replace President Charles de Gaulle and his Gaullist Party.Template:R

On 22 March far-left groups, a small number of prominent poets and musicians, and 150 students occupied an administration building at Paris University at Nanterre and held a meeting in the university council room dealing with class discrimination in French society and the political bureaucracy that controlled the university's funding. The university's administration called the police, who surrounded the university. After the publication of their wishes, the students left the building without any trouble. After this first record some leaders of what was named the "Movement of 22 March" were called together by the disciplinary committee of the university.

Events of May

Student strikes

Following months of conflicts between students and authorities at the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris (now Paris Nanterre University), the administration shut down the university on 2 May 1968.[17] Students at the Sorbonne campus of the University of Paris (today Sorbonne University) in Paris met on 3 May to protest against the closure and the threatened expulsion of several students at Nanterre.[18] On Monday, 6 May, the national student union, the Union Nationale des Étudiants de France (UNEF)—still the largest student union in France today—and the union of university teachers called a march to protest against the police invasion of Sorbonne. More than 20,000 students, teachers and supporters marched towards the Sorbonne, still sealed off by the police, who charged, wielding their batons, as soon as the marchers approached. While the crowd dispersed, some began to create barricades out of whatever was at hand, while others threw paving stones, forcing the police to retreat for a time. The police then responded with tear gas and charged the crowd again. Hundreds more students were arrested.

High school student unions spoke in support of the riots on 6 May. The next day, they joined the students, teachers and increasing numbers of young workers who gathered at the Arc de Triomphe to demand that:

- All criminal charges against arrested students be dropped,

- the police leave the university, and

- the authorities reopen Nanterre and Sorbonne.

Negotiations broke down, and students returned to their campuses after a false report that the government had agreed to reopen them, only to discover the police still occupying the schools. This led to a near revolutionary fervor among the students.

On Friday, 10 May, another huge crowd congregated on the Rive Gauche. When the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité again blocked them from crossing the river, the crowd again threw up barricades, which the police then attacked at 2:15 in the morning after negotiations once again floundered. The confrontation, which produced hundreds of arrests and injuries, lasted until dawn of the following day. The events were broadcast on radio as they occurred and the aftermath was shown on television the following day. Allegations were made that the police had participated in the riots, through agents provocateurs, by burning cars and throwing Molotov cocktails.[19]

The government's heavy-handed reaction brought on a wave of sympathy for the strikers. Many of the nation's more mainstream singers and poets joined after the police brutality came to light. American artists also began voicing support of the strikers. The major left union federations, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) and the Force Ouvrière (CGT-FO), called a one-day general strike and demonstration for Monday, 13 May.

Well over a million people marched through Paris on that day; the police stayed largely out of sight. Prime Minister Georges Pompidou personally announced the release of the prisoners and the reopening of the Sorbonne. However, the surge of strikes did not recede. Instead, the protesters became even more active.

When the Sorbonne reopened, students occupied it and declared it an autonomous "people's university". Public opinion at first supported the students, but quickly turned against them after their leaders, invited to appear on national television, "behaved like irresponsible utopianists who wanted to destroy the 'consumer society.'"Template:R Nonetheless, in the weeks that followed, approximately 401 popular action committees were set up in Paris and elsewhere to take up grievances against the government and French society, including the Sorbonne Occupation Committee.

Workers join the students

Template:Refimprove section In the following days, workers began occupying factories, starting with a sit-down strike at the Sud Aviation plant near the city of Nantes on 14 May, then another strike at a Renault parts plant near Rouen, which spread to the Renault manufacturing complexes at Flins in the Seine Valley and the Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt. Workers had occupied roughly fifty factories by 16 May, and 200,000 were on strike by 17 May. That figure snowballed to two million workers on strike the following day and then ten million, or roughly two-thirds of the French workforce, on strike the following week.

These strikes were not led by the union movement; on the contrary, the CGT tried to contain this spontaneous outbreak of militancy by channeling it into a struggle for higher wages and other economic demands. Workers put forward a broader, more political and more radical agenda, demanding the ousting of the government and President de Gaulle and attempting, in some cases, to run their factories. When the trade union leadership negotiated a 35% increase in the minimum wage, a 7% wage increase for other workers, and half normal pay for the time on strike with the major employers' associations, the workers occupying their factories refused to return to work and jeered their union leaders.[20][21] In fact, in the May '68 movement there was a lot of "anti-unionist euphoria,"[22] against the mainstream unions, the CGT, FO and CFDT, that were more willing to compromise with the powers that be than enact the will of the base.[13]

On 24 May two people died at the hands of the out of control rioters, in Lyon Police Inspector Rene Lacroix died when he crushed by a driverless truck sent careering into police lines by rioters and in Paris Phillipe Metherion, 26, was stabbed to death during an argument among demonstrators.[23]

On 25 May and 26 May, the Grenelle agreements were conducted at the Ministry of Social Affairs. They provided for an increase of the minimum wage by 25% and of average salaries by 10%. These offers were rejected, and the strike went on. The working class and top intellectuals were joining in solidarity for a major change in workers' rights.

On 27 May, the meeting of the UNEF, the most outstanding of the events of May 1968, proceeded and gathered 30,000 to 50,000 people in the Stade Sebastien Charlety. The meeting was extremely militant with speakers demanding the government be overthrown and elections held.

The Socialists saw an opportunity to act as a compromise between de Gaulle and the Communists. On 28 May, François Mitterrand of the Federation of the Democratic and Socialist Left declared that "there is no more state" and stated that he was ready to form a new government. He had received a surprisingly high 45% of the vote in the 1965 presidential election. On 29 May, Pierre Mendès France also stated that he was ready to form a new government; unlike Mitterrand he was willing to include the Communists. Although the Socialists did not have the Communists' ability to form large street demonstrations, they had more than 20% of the country's support.Template:RTemplate:R

De Gaulle flees

On the morning of 29 May, de Gaulle postponed the meeting of the Council of Ministers scheduled for that day and secretly removed his personal papers from Élysée Palace. He told his son-in-law Alain de Boissieu, "I do not want to give them a chance to attack the Élysée. It would be regrettable if blood were shed in my personal defense. I have decided to leave: nobody attacks an empty palace." De Gaulle refused Pompidou's request that he dissolve the National Assembly as he believed that their party, the Gaullists, would lose the resulting election. At 11:00 a.m., he told Pompidou, "I am the past; you are the future; I embrace you."[24]

The government announced that de Gaulle was going to his country home in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises before returning the next day, and rumors spread that he would prepare his resignation speech there. The presidential helicopter did not arrive in Colombey, however, and de Gaulle had told no one in the government where he was going. For more than six hours the world did not know where the French president was.[25] The canceling of the ministerial meeting, and the president's mysterious disappearance, stunned the French,Template:R including Pompidou, who shouted, "He has fled the country!"[26]

The national government had effectively ceased to function. Édouard Balladur later wrote that as prime minister, Pompidou "by himself was the whole government" as most officials were "an incoherent group of confabulators" who believed that revolution would soon occur. A friend of the prime minister offered him a weapon, saying, "You will need it"; Pompidou advised him to go home. One official reportedly began burning documents, while another asked an aide how far they could flee by automobile should revolutionaries seize fuel supplies. Withdrawing money from banks became difficult, gasoline for private automobiles was unavailable, and some people tried to obtain private planes or fake national identity cards.Template:R

Pompidou unsuccessfully requested that military radar be used to follow de Gaulle's two helicopters, but soon learned that he had gone to the headquarters of the French military in Germany, in Baden-Baden, to meet General Jacques Massu. Massu persuaded the discouraged de Gaulle to return to France; now knowing that he had the military's support, de Gaulle rescheduled the meeting of the Council of Ministers for the next day, 30 May,Template:R and returned to Colombey by 6:00 p.m.Template:R His wife Yvonne gave the family jewels to their son and daughter-in-law—who stayed in Baden for a few more days—for safekeeping, however, indicating that the de Gaulles still considered Germany a possible refuge. Massu kept as a state secret de Gaulle's loss of confidence until others disclosed it in 1982; until then most observers believed that his disappearance was intended to remind the French people of what they might lose. Although the disappearance was real and not intended as motivation, it indeed had such an effect on France.Template:R

On 30 May, 400,000 to 500,000 protesters (many more than the 50,000 the police were expecting) led by the CGT marched through Paris, chanting: "Adieu, de Gaulle!" ("Farewell, de Gaulle!"). Maurice Grimaud, head of the Paris police, played a key role in avoiding revolution by both speaking to and spying on the revolutionaries, and by carefully avoiding the use of force. While Communist leaders later denied that they had planned an armed uprising, and extreme militants only comprised 2% of the populace, they had overestimated de Gaulle's strength as shown by his escape to Germany.Template:R (One scholar, otherwise skeptical of the French Communists' willingness to maintain democracy after forming a government, has claimed that the "moderate, nonviolent and essentially antirevolutionary" Communists opposed revolution because they sincerely believed that the party must come to power through legal elections, not armed conflict that might provoke harsh repression from political opponents.)[27]

The movement was largely centered around the Paris metropolitan area, and not elsewhere. Had the rebellion occupied key public buildings in Paris, the government would have had to use force to retake them. The resulting casualties could have incited a revolution, with the military moving from the provinces to retake Paris as in 1871. Minister of Defence Pierre Messmer and Chief of the Defence Staff Michel Fourquet prepared for such an action, and Pompidou had ordered tanks to Issy-les-Moulineaux.Template:R While the military was free of revolutionary sentiment, using an army mostly of conscripts the same age as the revolutionaries would have been very dangerous for the government.Template:RTemplate:R A survey taken immediately after the crisis found that 20% of Frenchmen would have supported a revolution, 23% would have opposed it, and 57% would have avoided physical participation in the conflict. 33% would have fought a military intervention, while only 5% would have supported it and a majority of the country would have avoided any action.Template:R

At 2:30 p.m. on 30 May, Pompidou persuaded de Gaulle to dissolve the National Assembly and call a new election by threatening to resign. At 4:30 p.m., de Gaulle broadcast his own refusal to resign. He announced an election, scheduled for 23 June, and ordered workers to return to work, threatening to institute a state of emergency if they did not. The government had leaked to the media that the army was outside Paris. Immediately after the speech, about 800,000 supporters marched through the Champs-Élysées waving the national flag; the Gaullists had planned the rally for several days, which attracted a crowd of diverse ages, occupations, and politics. The Communists agreed to the election, and the threat of revolution was over.Template:RTemplate:R[28]

Events of June and July